American author Kate Chopin (1850–1904) wrote two published novels and about a hundred short stories in the 1890s. Most of her fiction is set in Louisiana and most of her best-known work focuses on the lives of sensitive, intelligent women.

By the Editors of KateChopin.org

Kate Chopin’s short stories were well received in her own time and were published by some of America’s most prestigious magazines—Vogue, the Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Young People, Youth’s Companion, and the Century. A few stories were syndicated by the American Press Association. Her stories appeared also in her two published collections, Bayou Folk (1894) and A Night in Acadie (1897), both of which received good reviews from critics across the country. Twenty-six of her stories are children’s stories—those published in or submitted to children’s magazines or those similar in subject or theme to those that were. By the late 1890s Kate Chopin was well known among American readers of magazine fiction.

Her early novel At Fault (1890) had not been much noticed by the public, but The Awakening (1899) was widely condemned. Critics called it morbid, vulgar, and disagreeable. Willa Cather, who would become a well known twentieth-century American author, labeled it trite and sordid.

Some modern scholars have written that the novel was banned at Chopin’s hometown library in St. Louis, but this claim has not been able to be verified, although in 1902, the Evanston, Illinois, Public Library removed The Awakening from its open shelves—and the book has been challenged twice in recent years. Chopin’s third collection of stories, to have been called A Vocation and a Voice, was for unknown reasons cancelled by the publisher and did not appear as a separate volume until 1991.

Chopin’s novels were mostly forgotten after her death in 1904, but several of her short stories appeared in an anthology within five years after her death, others were reprinted over the years, and slowly people again came to read her. In the 1930s a Chopin biography appeared which spoke well of her short fiction but dismissed The Awakening as unfortunate. However, by the 1950s scholars and others recognized that the novel is an insightful and moving work of fiction. Such readers set in motion a Kate Chopin revival, one of the more remarkable literary revivals in the United States.

After 1969, when Per Seyersted’s biography, one sympathetic to The Awakening, was published, along with Seyersted’s edition of her complete works, Kate Chopin became known throughout the world. She has attracted great attention from scholars and students, and her work has been translated into other languages, including Albanian, Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Dutch, French, Galician, German, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Malayalam, Persian (Farsi), Polish, Portuguese, Serbian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Vietnamese. (If you know of a translation into another language, would you write to us?) She is today understood as a classic writer who speaks eloquently to contemporary concerns. The Awakening, “The Storm,” “The Story of an Hour,” “Désirée’s Baby,” “A Pair of Silk Stockings,” “A Respectable Woman,” “Athénaïse,” and other stories appear in countless editions and are embraced by people for their sensitive, graceful, poetic depictions of women’s lives.

Kate Chopin’s childhood

Kate Chopin’s marriage; her life in Louisiana

Kate Chopin’s writing career; her life in St. Louis

Kate Chopin’s death; assessments of her work

Published biographies of Kate Chopin

Questions and Answers

Kate Chopin’s childhood

Catherine (Kate) O’Flaherty was born in St. Louis, Missouri, USA, on February 8, 1850, the second child of Thomas O’Flaherty of County Galway, Ireland, and Eliza Faris of St. Louis. Kate’s family on her mother’s side was of French extraction, and Kate grew up speaking both French and English. She was bilingual and bicultural–feeling at home in different communities with quite different values–and the influence of French life and literature on her thinking is noticeable throughout her fiction.

From 1855 to 1868 Kate attended the St. Louis Academy of the Sacred Heart, with one year at the Academy of the Visitation. As a girl, she was mentored by woman–by her mother, her grandmother, and her great grandmother, as well as by the Sacred Heart nuns. Kate formed deep bonds with her family members, with the sisters who taught her at school, and with her life-long friend Kitty Garasché. Much of the fiction Kate wrote as an adult draws on the nurturing she received from women as she was growing up.

Her early life had a great deal of trauma. In 1855, her father was killed in a railroad accident. In 1863 her beloved French-speaking great grandmother died. Kate spent the Civil War in St. Louis, a city where residents supported both the Union and the Confederacy and where her family had slaves in the house. Her half brother enlisted in the Confederate army, was captured by Union forces, and died of typhoid fever.

From 1867 to 1870 Kate kept a commonplace book in which she recorded diary entries and copied passages of essays, poems, and other writings. In 1869 she wrote a little sketch, “Emancipation: A Life Fable.”

Kate Chopin’s marriage; her life in Louisiana

At eighteen, Kate was an “Irish Beauty,” her friend Kitty later said, with “a droll gift of mimicry” and a passion for music. At about nineteen, through social events held at Oakland, a wealthy estate near St. Louis, Kate met Oscar Chopin of Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, whose French father had taken the family to Europe during the Civil War. “I am going to be married,” Kate confided in her commonplace book, “married to the right man. It does not seem strange as I had thought it would–I feel perfectly calm, perfectly collected. And how surprised everyone was, for I had kept it so secret!” Kate and Oscar were married in 1870.

At eighteen, Kate was an “Irish Beauty,” her friend Kitty later said, with “a droll gift of mimicry” and a passion for music. At about nineteen, through social events held at Oakland, a wealthy estate near St. Louis, Kate met Oscar Chopin of Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, whose French father had taken the family to Europe during the Civil War. “I am going to be married,” Kate confided in her commonplace book, “married to the right man. It does not seem strange as I had thought it would–I feel perfectly calm, perfectly collected. And how surprised everyone was, for I had kept it so secret!” Kate and Oscar were married in 1870.

On their wedding trip the couple traveled to Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and New York, and then crossed the Atlantic and landed in Bremen, Germany. Dr. Heidi M. Podlasli-Labrenz, a Senior Lecturer at the University of Bremen, recently took pictures, she tells us, “of the place that Kate Chopin visited on July 8, 1870: ‘Ten miles out in the country’ . . . to visit the residence of a Mr Knoop, the wealthiest merchant of Bremen.'” Podlasli-Labrenz says that from the picture she took of Baron Knoop’s statue “you will get an idea of the kind of man he was supposed to have been: very polite, generous, and good-natured.”

The Chopins toured Germany, Switzerland, and France. They saw Paris only briefly, in September, 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, at a moment when the city was preparing for a long siege. Kate never visited Europe again.

Back in the States, the couple settled in New Orleans, where Oscar established a business as a cotton factor, dealing with cotton and other commodities (corn, sugar, and molasses, among them). Louisiana was in the midst of Reconstruction at the time, and the city was beset with economic and racial troubles. Oscar joined the notorious White League, a Democratic group that in 1874 had a violent confrontation with Republican Radicals, causing President Grant to send in federal troops.

But New Orleans also offered superb music at the French Opera House, along with fine theatre, horse races, and, of course, Mardi Gras. Kate may have met the French painter Edgar Degas, who lived in New Orleans for several months around 1872. She would have been observing life in the city, gathering material that she could draw upon for her fiction later in life.

The Chopins lived in three New Orleans houses. The last one, pictured here, is at 1413 Louisiana Avenue (The photo by Judy Cooper appears in Thomas Bonner, Jr’s Kate Chopin Companion):

Like other wealthy families in the city, the Chopins would go by boat to vacation on Grand Isle, a Creole resort in the Gulf of Mexico.

Between 1871 and 1879 Kate gave birth to five sons and a daughter–in order of birth, Jean Baptiste, Oscar Charles, George Francis, Frederick, Felix Andrew, and Lélia (baptized Marie Laïza).

In 1879 the Chopins moved to Cloutierville, a small French village in Natchitoches Parish, in northwestern Louisiana, after Oscar closed his New Orleans business because of hard financial times. The house, later called the Bayou Folk Museum/Kate Chopin House, burned in 2008. (Photo by Jean Carter, courtesy Cane River National Heritage Area.)

Kate Chopin’s writing career; her life in St. Louis

Oscar bought a general store in Cloutierville, but in 1882 he died of malaria–and Kate became a widow at age thirty-two, with the responsibility of raising six children. She never remarried.

In 1883 and 1884, Chopin’s recent biographer, Emily Toth, has written, Kate had an affair with a local planter. But she then moved with her family back to St. Louis where she found better schools for her children and a richer cultural life for herself. Shortly after, in 1885, her mother died. Kate Chopin’s home was at 4232 McPherson Avenue in St Louis; it is still lived in today.

As a mature adult, Barbara Ewell writes, Kate “was a remarkable, charming person. Not very tall, inclined to be plump, and quite pretty, she had thick, wavy brown hair that grayed prematurely, and direct, sparking brown eyes. Her friends remembered most her quiet manner and quick Irish wit, embellished with a gift for mimicry. A gracious, easygoing hostess, she enjoyed laughter, music, and dancing, but especially intellectual talk, and she could express her own considered opinions with surprising directness.”

Dr. Frederick Kolbenheyer, her obstetrician and a family friend, encouraged her to write. Influenced by Guy de Maupassant and other writers, French and American, Kate began to compose fiction, and in 1889 one of her stories appeared in the St. Louis Post Dispatch. In 1890 her first novel, At Fault, was published privately.

The book is about a thirtyish Catholic widow in love with a divorced man. Like Edna Pontellier in The Awakening, Thérèse Lafirme struggles to reconcile her “outward existence” with her “inward life.” She cannot as a practicing Catholic accept the idea of divorce, yet she cannot banish from her life the man whom she loves. At Fault offers a compelling glimpse into what Kate Chopin was thinking about as she began her writing career.

Chopin completed a second novel, to have been called Young Dr. Gosse and Théo, but her attempt to find a publisher failed and she later destroyed the manuscript. She became active in St. Louis literary and cultural circles, discussing the works of many writers, including Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Émile Zola, and George Sand (she had called her daughter Lélia, apparently after the title of Sand’s 1833 novel).

During the next decade, although maintaining an active social life, she plunged into her work and kept accurate records of when she wrote her hundred or so short stories, which magazines she submitted them to, when they were accepted (or rejected) and published, and how much she was paid for them.

In 1889 she wrote “A Point at Issue!” and in 1891 rewrote “A No-Account Creole” (which she had originally written in 1888) and wrote the children’s story “Beyond the Bayou” and other stories. Five of her stories appeared in regional and national magazines, including Youth’s Companion and Harper’s Young People.

She wrote “Désirée’s Baby” and the little sketch “Ripe Figs” in 1892. “At the ‘Cadian Ball” appeared in Two Tales that year, and eight of her other stories were published. The next year she wrote “Madame Célestin’s Divorce,” and thirteen of her stories were published. Chopin traveled to New York and Boston to seek a publisher for a novel and a collection of stories.

In 1894 she wrote “Lilacs” and “Her Letters.” “The Story of an Hour” and “A Respectable Woman” appeared in Vogue. And Houghton Mifflin published Bayou Folk, a collection of twenty-three of Chopin’s stories.

Bayou Folk was a success. Chopin wrote that she had seen a hundred press notices about it. The collection was written up in the New York Times and the Atlantic, among other places, and most reviewers found its stories pleasant and charming. They liked its use of local dialects.

Chopin traveled that year to a conference of the Western Association of Writers in Indiana and published in Critic an essay about her experience, an essay that offers a rare insight into what she thinks about writers and writing. “Among these people,” she says, “are to be found an earnestness in the acquirement and dissemination of book-learning, a clinging to the past and conventional standards, an almost Creolean sensitiveness to criticism and a singular ignorance of, or disregard for, the value of the highest art forms.”

“There is,” she continues, “a very, very big world lying not wholly in northern Indiana, nor does it lie at the antipodes, either. It is human existence in its subtle, complex, true meaning, stripped of the veil with which ethical and conventional standards have draped it.”

Also in 1894 Chopin published in St. Louis Life a review of Lourdes by the French writer Émile Zola. She did not much like the book, but the way she begins her review is illuminating:

“I once heard a devotee of impressionism admit, in looking at a picture by Monet, that, while he himself had never seen in nature the peculiar yellows and reds therein depicted, he was convinced that Monet had painted them because he saw them and because they were true. With something of a kindred faith in the sincerity of Mons. Zola’s work, I am yet not at all times ready to admit its truth, which is only equivalent to saying that our points of view differ, that truth rests upon a shifting basis and is apt to be kaleidoscopic.”

Her 1894 comment about the importance of describing “human existence in its subtle, complex, true meaning, stripped of the veil with which ethical and conventional standards have draped it” and her conviction that “truth rests upon a shifting basis and is apt to be kaleidoscopic” are helpful points of reference in approaching Kate Chopin’s work.

In 1895 Chopin wrote “Athénaïse” and “Fedora,” and twelve of her stories were published. In 1896 she wrote “A Pair of Silk Stockings.” “Athénaïse” was published in the Atlantic Monthly. In 1897 Way and Williams (of Chicago) published A Night in Acadie, a collection of twenty-one Chopin stories.

In 1895 Chopin wrote “Athénaïse” and “Fedora,” and twelve of her stories were published. In 1896 she wrote “A Pair of Silk Stockings.” “Athénaïse” was published in the Atlantic Monthly. In 1897 Way and Williams (of Chicago) published A Night in Acadie, a collection of twenty-one Chopin stories.

Like Bayou Folk, her earlier collection, A Night in Acadie was praised by the critics. One reviewer called it “a string of little jewels,” and a modern critic considers it one of America’s great nineteenth-century books of short stories.

Chopin’s grandmother, Athénaïse Charleville Faris, died in 1897. Chopin worked on The Awakening that year, finishing the novel in 1898. She also wrote her short story “The Storm” in 1898, but, apparently because of its sexual content, she did not send it out to publishers. Probably no mainstream American publisher would have printed the story.

The next year, 1899, one of her stories appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, and Herbert S. Stone published The Awakening.

A few critics praised the novel’s artistry, but most were very negative, calling the book “morbid,” “unpleasant,” “unhealthy,” “sordid,” “poison.” You can read about the reviewers in the Chopin biographies listed below, in Margo Culley’s Norton Critical Edition of the novel, and in Janet Beer’s Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin, among other places. For details, scroll down on The Awakening page of this site.

It took decades before critics fully grasped what Chopin had accomplished. In 1969 Norwegian critic Per Seyersted finally did her justice. Kate Chopin, he wrote, “broke new ground in American literature. She was the first woman writer in her country to accept passion as a legitimate subject for serious, outspoken fiction. Revolting against tradition and authority; with a daring which we can hardy fathom today; with an uncompromising honesty and no trace of sensationalism, she undertook to give the unsparing truth about woman’s submerged life. She was something of a pioneer in the amoral treatment of sexuality, of divorce, and of woman’s urge for an existential authenticity. She is in many respects a modern writer, particularly in her awareness of the complexities of truth and the complications of freedom.”

Two of Chopin’s stories were published in Vogue in 1900. You can find out when Kate Chopin wrote each of her short stories and when and where each was first published.

Herbert S. Stone, for unknown reasons, canceled her contract for A Vocation and a Voice, a third collection of her stories (the collection was published by Penguin Classics in 1991). In 1902 “A Vocation and a Voice,” the title story of Chopin’s proposed volume, was published in the St. Louis Mirror.

Kate Chopin’s death; assessments of her work

In 1904 Kate Chopin bought a season ticket for the famous St. Louis World’s Fair, which was located not far from her home. It had been hot in the city all that summer, and Saturday, August 20, was especially hot, so when Chopin returned home from the fair, she was very tired. She called her son at midnight complaining of a pain in her head. Doctors thought that she had had a cerebral hemorrhage.

She lapsed into unconsciousness the next day and died on August 22. She is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, where many people visit her gravesite and sometimes leave behind tokens of their affection.

Her last published story appeared in Youth’s Companion on March 30, 1905. You can read “Her First Party” as it looked when it appeared.

Fifty years later, critics began to understand the essence of her work. Kenneth Eble published an article about her in 1956, and, in his introduction to a paperback edition of The Awakening in 1964, he speaks of Chopin’s “underground imagination”–“the imaginative life which seems to have gone on from early childhood somewhat beneath and apart from her well-regulated actual existence.”

George Arms a few years later writes that in her work Kate Chopin “presents a series of events in which the truth is present, but with a philosophical pragmatism she is unwilling to extract a final truth. Rather, she sees truth as constantly re-forming itself and as so much a part of the context of what happens that it can never be final or for that matter abstractly stated.”

And in his 1969 biography, Per Seyersted famously described how Chopin “broke new ground in American literature.”

Since 1969, countless scholars have written about Chopin’s life and work. Feminist critics have had an enormous influence. Most of what has been written about Kate Chopin since 1969 is feminist in nature or is focused on women’s positions in society. Sandra Gilbert’s introduction to the Penguin Classics Edition of The Awakening, for example, and Margo Culley’s selection of essays for the Norton Critical Edition of the novel are familiar to a generation of readers, although scholars have also been dealing with other subjects and themes. Lists of critical works appear at the bottom of those pages on this site devoted to Chopin’s two novels and her most popular short stories.

Today Kate Chopin is widely accepted as one of America’s essential authors.

Her novels and stories are available in countless books and online. Critics and scholars in many countries have discussed her work in over 400 journal articles as well as in at least 60 books and 160 PhD dissertations. Artists have created plays, films, songs, operas, dances, screenplays, graphic fiction, and other art forms based on her work.

The Central West End Association of the city of St. Louis, Missouri, in 2012 dedicated a bust of Kate Chopin at the Writers’ Corner in the city.

Published biographies of Kate Chopin:

The most recent–and today by far the most influential–biography of Kate Chopin is Emily Toth’s Unveiling Kate Chopin (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999). Emily Toth earlier published a longer biography, Kate Chopin (New York: Morrow, 1990).

An important biography is the one referred to above, Per Seyersted’s Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969).

Also important is Daniel Rankin’s Kate Chopin and Her Creole Stories (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1932; available now through Google Books). In spite of his impaired critical judgment (he considered The Awakening an unfortunate mistake), Rankin had, as Bernard Koloski explains in the recent Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin, “what no other Chopin scholar would ever have again: access to Kate Chopin’s children, relatives, friends, and at least one of her publishers.”

Biographical questions and answers:

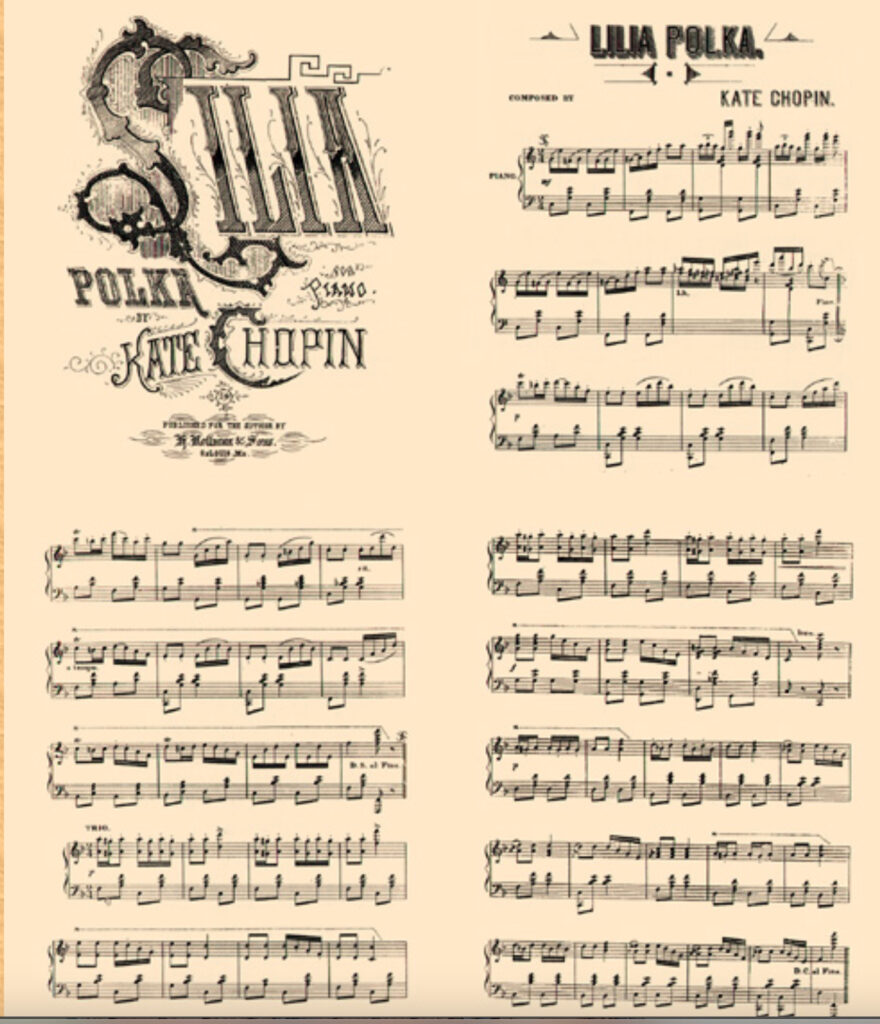

Q: I associate the name “Chopin” with piano music, not fiction. Did Kate Chopin write any music?

A: Yes, before she started writing fiction, she wrote a polka called the “Lilia Polka.” It was published by H. Rollman & Sons in 1888.

You can hear the polka played on a piano.

Q: Does Kate Chopin have any descendants living today?

A: Yes, she has many. You can read about some of them on our page Kate Chopin’s Family Today.

Q: I’m reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and I’ve just met Simon Legree. I’ve read somewhere that Simon Legree was modeled after the father of Oscar Chopin, Kate Chopin’s husband. Do you know if this is true or just rumor?

A: Here is what Emily Toth says in her 1990 biography of Kate Chopin: “Local folklore confused [Dr. Chopin, Oscar Chopin’s father] with Robert McAlpin, who had owned the land before him and who was sometimes said to be the model for Simon Legree in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

So the connection between Oscar Chopin’s father and Simon Legree is rumor, not fact.

You may want to read Chopin’s early novel, At Fault. It includes a chapter in which two characters visit Robert McAlpin’s grave.

Q: Can anyone help with the identity of Mrs. F. M. Estere of 4434 Laclede Avenue of St. Louis and her possible connection with Kate Chopin?

A: We’ve recently received a response to this question. Many thanks to Ms. Clark:

I am a genealogist and was intrigued by the question. Here is what I was able to find out in just a couple of hours of Internet research…..

I believe the woman is Mrs. F. M. Estes (Francis “Frank” Marion Estes). He was a lawyer who practiced at that address. This was his second wife. They married in 1896 in St. Louis. Her name was Nellie Hancock Stockton (1870-1943) She was born in Texas. They had one son, Stockton. Frank died in 1909. He had many investments so his wife never wanted for money after his death. She actually left the country in 1910 and went to Buenos Aires until about 1912. She moved to New York after that. She left the country again in 1918 and returned in 1921. Her son was traveling with her at this time as he is listed on the ship’s manifest. Frank had two children from his first marriage, Francis M. Jr, and Grace.

Kate’s house on Morgan Street was several blocks away from the Estes home on Laclede Ave. Her home on McPhearson was much closer. It is possible they were in the same social circles. Frank was a well-known lawyer and was the council on several important St. Louis cases. It is possible he represented Kate at some time.

I hope this information sheds some light on Kate’s friends.

Pamela Clark

New Q: Hello from Galway, Ireland. I wonder what amount of detail is known about Kate Chopin’s father Thomas O’Flaherty’s birthplace, and about his wife’s birthplace — the townlands in which they were born, and their own parents’ details?

A: Several Chopin scholars agree that your best beginning point for understanding more about Kate Chopin’s father is in the book Unveiling Kate Chopin, the 1999 biography by Emily Toth. You should be able to find a copy of this book through any good library or bookstore.

Emily Toth writes: “I don’t know if anyone’s checked Irish baptismal records for Thomas O’Flaherty family. Churches in Ireland do keep records forever, so you might be able to find names of siblings and godparents. I remember wondering long ago if there were Protestant connections, since he was allegedly well educated at a time when most Catholics (such as my Irish ancestors) were illiterate. It would be great if there’s any more information.”

Tom Bonner adds: “I had a friend who was having difficulty locating a line of ancestry in Ireland. Finally, he contacted the embassy for Ireland in Washington, and the person who was assigned to his query provided resources and directions that expedited his search. I think that knowing more about Chopin’s father would, indeed, be helpful.”

And Bonnie Shaker writes that “based on papers for the Ireland conference panel on Irishness in Kate Chopin’s fiction, the best starting points are still Emily Toth’s biographies.”