“The Story of an Hour” is Kate Chopin’s short story about the thoughts of a woman after she is told that her husband has died in an accident. The story first appeared in Vogue in 1894 and is today one of Chopin’s most popular works.

By the Editors of KateChopin.org

Read the story online

New Kate Chopin’s popularity

Characters

Time and place

Themes

When the story was written and published

What critics and scholars say

New Questions and answers

Accurate texts

All of Kate Chopin’s short stories in Spanish

Books about the story

Articles about the story

A graphic version of the story

A Christmas opera based on the story

Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” online and in print

You can read the story in our online text. If you’re citing a passage from this or other Kate Chopin stories for research purposes, it’s a good idea to check your citation against one of these printed texts. This is especially important with “The Story of an Hour,” because some online versions of the story — and some published versions — omit a word that changes the meaning of what Kate Chopin is saying.

In the middle of the story, some online versions’ sentence reads, “There would be no one to live for during those coming years; she would live for herself.” Compare that with the sentence as it appears in our online text: “There would be no one to live for her during those coming years; she would live for herself.” If you don’t see why the word matters, or if you want to understand why there are two versions of the story, check our questions and answers below.

“The Story of an Hour” characters

- Louise Mallard

- Brently Mallard: husband of Louise

- Josephine: sister of Louise

- Richards: friend of Brently Mallard

“The Story of an Hour” time and place

The story is set in the late nineteenth century in the Mallard residence, the home of Brently and Louise Mallard. More about the location is not specified.

“The Story of an Hour” themes

Readers and scholars often focus on the idea of freedom in “The Story of an Hour,” on selfhood, self-fulfillment, the meaning of love, or what Chopin calls the “possession of self-assertion.” There are further details in what critics and scholars say and in the questions and answers below. And you can read about finding themes in Kate Chopin’s stories and novels on the Themes page of this site.

When Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” was written and published

It was written on April 19, 1894, and first published in Vogue on December 6, 1894, under the title “The Dream of an Hour,” one of nineteen Kate Chopin stories that Vogue published. It was reprinted in St. Louis Life on January 5, 1895. The St. Louis Life version includes several changes in the text. As we explain in the questions and answers section of this page, it includes the word “her.”

You can find out when Kate Chopin wrote each of her short stories and when and where each was first published.

What critics and scholars say about “The Story of an Hour”

A great deal has been written about this story for many years. Some representative comments:

The story is “one of feminism’s sacred texts,” Susan Cahill writing in 1975, when readers were first discovering Kate Chopin.

“Love has been, for Louise and others, the primary purpose of life, but through her new perspective, Louise comprehends that ‘love, the unsolved mystery’ counts for very little. . . . Love is not a substitute for selfhood; indeed, selfhood is love’s precondition.” Barbara C. Ewell

“Mrs. Mallard will grieve for the husband who had loved her but will eventually revel in the ‘monstrous joy’ of self-fulfillment, beyond ideological strictures and the repressive effects of love.” Mary Papke

Kate Chopin “was a life-long connoisseur of rickety marriages, and all her wisdom is on display in her piercing analysis of this thoroughly average one.” Christopher Benfey

“In the mid- to late 1890s, Vogue was the place where Chopin published her most daring and surprising stories [‘The Story of an Hour’ and eighteen others]. . . . Because she had Vogue as a market — and a well-paying one — Kate Chopin wrote the critical, ironic, brilliant stories about women for which she is known today. Alone among magazines of the 1890s, Vogue published fearless and truthful portrayals of women’s lives.” Emily Toth

Her husband’s death forces Louise to reconcile her “inside” and “outside” consciousness — a female double consciousness within Louise’s thoughts. Though constrained by biological determinism, social conditioning, and marriage, Louise reclaims her own life — but at a price. Her death is the result of the complications in uniting both halves of her world. Angelyn Mitchell

Louise Mallard’s death isn’t caused by her joy at seeing her husband’s return or by her sudden realization that his death has granted her autonomy. She dies as a result of the strain she is under. The irony of her death is that even if her sudden epiphany is freeing, her autonomy is empty, because she has no place in society. Mark Cunningham

Louise’s death is the culmination of her being “an immature and shallow egotist,” Lawrence Berkove says. He focuses on the scene in Louise’s bedroom and points out how unrealistic her notion of love is. Her death, he writes, is the only place that will offer her the absolute freedom she desires.

“This astonishing story strongly indicates that the sudden success which [the publication in 1894 of] Bayou Folk brought Kate Chopin was of crucial importance in the author’s own self-fulfillment. It gave her a certain release from what she evidently felt as repression or frustration, thereby freeing forces that had lain dormant in her. It is highly significant that she wrote ‘The Story of an Hour,’ an extreme example of the theme of self-assertion, at the exact moment when the first reviews of the book had both satisfied and increased her secret ambitions.” Per Seyersted

You can search the titles in our extensive databases of books and articles for more information about this short story — information in English, German, Portuguese, and Spanish.

Questions and answers about “The Story of an Hour”

Q: I don’t understand what you mean about what happens if “her” is left out of the sentence at the top of the page, “There would be no one to live for her during those coming years; she would live for herself.” How does including “her” change the meaning of the sentence?

A: Without “her,” the sentence means that Louise Mallard has been living for her husband, that he has been the center of her life, that he has been her reason for living. With “her,” the sentence means that Brently Mallard has been controlling his wife’s life, that his “powerful will [has been] bending hers” to his, has been bending what she wants to what he wants, has been forcing her to live the way he wants her to live, to do what he wants her to do.

That’s an important distinction. “Her” in the sentence explains what Mrs. Mallard means by her newly recognized “possession of self-assertion,” what she means by whispering, “Free! Body and soul free!”

Q: Why are there two versions of that sentence, with and without the “her”?

A: When the story was published in Vogue in 1894, the word “her” was not included. It’s not clear if “her” was in the copy Kate Chopin sent to Vogue or if the Vogue editor or printer left it out intentionally or accidentally. Some printed versions and some websites today use the Vogue version. You can see the sentence in question three lines down on the right column:

The story was reprinted the following year in St. Louis Life, which was edited by Sue V. Moore. Emily Toth, Chopin’s latest biographer, refers to Moore as “Kate’s friend” and a women who had promoted Chopin’s work for years. A clipping of the Vogue story pasted on a sheet of paper (and preserved now in the Missouri History Museum) shows two handwritten changes, one of which is the inserted word “her,” and the St. Louis Life version of the story includes those two changes, along with a few others (we are grateful to the staff of the St. Louis Public Library for providing us with this copy), You can see the sentence in question four lines down on the right column:

Daniel Rankin, Chopin’s earliest biographer, says those changes were “made by the author.” Per Seyersted, who edited the Complete Works of Kate Chopin, says they were “very likely made by the editor [Sue V. Moore].” Seyersted, nevertheless, included the two changes in his text of the story in the Complete Works. We use Seyersted’s text here. We include the “her.” Many printed sources and other websites include it, too.

Q: You say that the story was first published under the title, “The Dream of an Hour.” Who changed that title and why?

A: We can probably identify who changed it, but we don’t know why. The story appeared in Vogue in 1894 as “The Dream of an Hour.” Even as late as 1962, critic Edmund Wilson continued to refer to it under this title. But in 1969 it was called “The Story of an Hour” in the Complete Works of Kate Chopin.

It seems likely that Per Seyersted, who edited the Complete Works, changed the title, perhaps because Kate Chopin referred to “The Story of an Hour” in one of the two account books where she recorded how much she earned for each of her stories. In the other account book, she referred to the story as “The Dream of an Hour.” (Chopin’s account books are preserved in the Missouri History Museum and are transcribed in Kate Chopin’s Private Papers.)

It may be, however, that if Seyersted changed the title, he did so because a clipping of the Vogue story pasted on a sheet of paper (and housed now in the Missouri History Museum) has the word “Dream” crossed out and the word “Story” inserted.

Q: What does the present title mean?

A: The action of the story seems to play out in about an hour’s time.

Q: Do you know how much Vogue magazine paid Kate Chopin for the story?

Yes. Kate Chopin recorded in two account books how much she earned for each of her stories and novels. Vogue paid her $10 for “The Dream of an Hour,” the title under which the story appeared. Because of inflation (the usual increase in the level of prices), that $10 in 1894 would be worth about $372 today.

Q: Is it true that this is Kate Chopin’s most popular story?

A: It probably is true. The story certainly appears in a great many anthologies these days. Kate Chopin’s sensitivity to what it sometimes feels like to be a woman is on prominent display in this work — as it is in The Awakening. Chopin’s often-celebrated yearning for freedom is also on display here–as is her sense of ambiguity and her complex way of seeing life, of seeing, for example, that it is both “men and women” who “believe they have a right to impose a private will upon a fellow-creature.”

From 1929 to about 1970, “Désirée’s Baby” was the best known of Chopin’s works, praised by critics and often reprinted. When the Complete Works of Kate Chopin was published in 1969, “The Storm”–unknown until that time–became famous almost overnight, as did “The Story of an Hour.” Today “Désirée’s Baby,” “The Story of an Hour,” and “The Storm,” are heavily discussed by scholars and regularly read in university and secondary school classes around the world, although a few other stories–among them “A Respectable Woman,” “Lilacs,” “A Pair of Silk Stockings,” “Athénaïse,” and “At the ‘Cadian Ball”–are also frequently read.

Q: I’ve read on a website that readers were scandalized by the story when it was published. Why?

A: It’s a mystery to us how the authors of that website could possibly know that readers in the 1890s were, in fact, scandalized by the story. Book reviewers were certainly upset by Kate Chopin’s novel The Awakening in 1899. There are published reviews showing that. There is, however–so far as we can tell–no printed evidence that the “The Story of an Hour” set off a scandal among readers.

Nevertheless, it is true that, as Emily Toth says in Unveiling Kate Chopin, “Kate Chopin had to disguise reality. She had to have her heroine die. A story in which an unhappy wife is suddenly widowed, becomes rich, and lives happily ever after . . . would have been much too radical, far too threatening in the 1890s. There were limits to what editors would publish, and what audiences would accept.”

New Q: Some students in my class think that Mrs. Mallard planned her husband’s death. Is there any evidence that she did?

A: If this were real life — if you knew Mrs. Mallard, if you had been a friend or a relative of hers, if you understood the way she thinks and watched the way she has been acting throughout her life — then maybe you could find some evidence to help you answer your question.

But “The Story of an Hour” is fiction. It’s a work of art.

One advantage of art — of a story, a film, a song, etc. — is that it can let us see something that we could not see any other way. In this story, for example, we can see inside of Mrs. Mallard’s mind to know exactly what she is thinking for that one hour in her life. That’s something we almost never know about another person, just as other people almost never know exactly what we’re thinking.

So a good story, a good work of art, is like a gift. It gives us something special.

But one disadvantage of art — of a story, a film, a song, etc. — is that what it gives us is all we have. We don’t know anything more about Mrs. Mallard than what we have in those words of the story. We can’t know any more about her, because there is nothing more to know. If Kate Chopin had written other stories about Mrs. Mallard in which she told us more about her life and what kind of person she is, then maybe we could better answer the question.

But this is the only story in which Kate Chopin writes about Mrs. Mallard. If you read the story again, if you study the words in it carefully, you’ll see that there is no evidence that Mrs. Mallard planned her husband’s death. So we have to conclude that she did not. If Kate Chopin had wanted us to know that she did, then she would have told us that in the story.

New Q: This webpage has so many words on it! Why don’t you add some pictures or videos or podcasts?

A: Sorry to hear you are disappointed in this webpage.

We explain on this page what our readers over the past 20 years have been asking us about. Our readers are students, teachers, librarians, journalists, playwrights, filmmakers, translators, book club members, bloggers, podcast hosts, influencers,and other people in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Philippines, India, China, Brazil, and dozens of other countries around the world.

On this page and our other pages devoted to one of Kate Chopin’s short stories or novels, we describe in lots of short paragraphs what our readers have wanted to know. About 25% of our readers are not native speakers of English. So we try to answer their questions in English that is easy to understand.

We include at the top of a page like this a list of red links so our readers can get quickly to what exactly it is they need to know.

But you might try looking at some other pages on our site: Our page, for example, where you can watch three short films based on Kate Chopin’s stories. Or our page in which we link to a video where you can listen to a song Kate Chopin wrote. Or our page in which we link to a podcast where you can hear specialists talk about Kate Chopin’s stories. Or our News page in which you will find lots of images and colors.

Q: I’m studying literature in France and am looking for a film adaptation of “The Story of an Hour.” Does one exist?

A: Thomas Bonner, Jr. (Xavier University of Louisiana) offers this response:

The Joy That Kills was produced by Cypress Productions in 1984 and released the following year as part of the Public Broadcast System’s American Playhouse series. Tina Rathborne (sometimes spelled Rathbone or Rathbourne) directed; she and Nancy Dyer wrote the script. Set in New Orleans in the 1870s, the film does not follow the almost existential lack of a specific setting and time in “The Story of an Hour.” It leans toward the New Orleans settings of The Awakening. It was filmed in one of the historic houses in the French Quarter of New Orleans with Ann Masson being the film’s art director. I always felt that the story, if it has a specific setting, is closer to the St. Louis area as it evokes Chopin’s loss of her father in a train wreck and that the film helped explicate The Awakening more than the story.

And Emily Toth (Louisiana State University) adds that “there’s at least one other film of ‘The Story of an Hour,’ by Ishtar Films.”

Q: Do you happen to know if “The Story of an Hour” is published in any Swedish book or magazine? I have found it online (Swedish title: Berättelsen om en timme), but nowhere in print. I have an old photocopy of the short story, which is obviously from a book, but no one I have talked to (including librarians) knows where it is from.

A: We have found no answer to this question. If you have useful information, would you contact us?

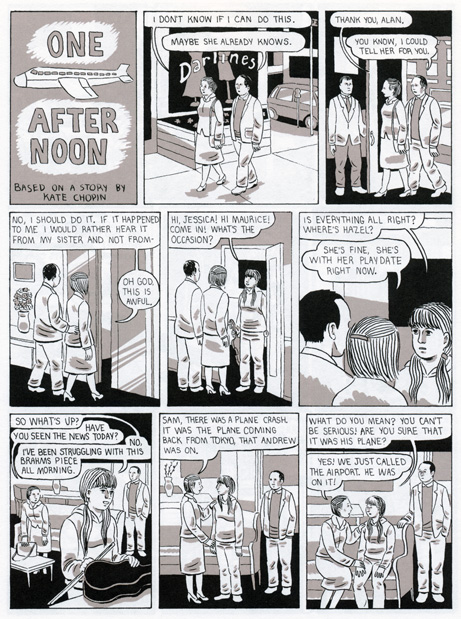

A Graphic Short Story Based on “The Story of an Hour”

Cartoonist Gabrielle Bell’s Cecil and Jordan in New York (Drawn and Quarterly, 2009) is a collection of graphic short stories.

Here is the first page of a story called “One Afternoon,” based on Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour”:

Gabrielle Bell reimagines “The Story of an Hour” within a larger narrative, which, the New York Times says, “is narrated by a young woman who’s just moved to the city with her filmmaker boyfriend; it’s a clear-cut tale of impecunious 20-something artists until halfway through, when the narrator abruptly transforms herself into a chair, gets taken home by someone who finds her on the sidewalk and decides that her old life won’t miss her. The engine of these mercilessly observed stories is squirminess: emotional awkwardness so intense that it can erupt into magic or just knot itself into scars.”

A Christmas Opera Based on “The Story of an Hour”

In December, 2019, the Gramercy Opera in New York at Brooklyn’s Montauk Club presented an opera “Story of an Hour.” The opera company’s announcement read:

“Based on the 1894 short story by Kate Chopin, in a classic operetta-esque style, ‘Story of an Hour’ is a one-act opera set in the 1800s during the Christmas season. It follows the story of a fatal train accident and the consequences it has on two young women — one of whose husbands is believed to have been on the train.”

“Story of an Hour” was the winner of the inaugural Salzman-Gramercy Opera Advancement Prize. The music was written by Michael Valenti and the libretto by Kleban- and Stacey Luftig. The cast included Kate Fruchterman, Sable Strout, Aaron Theno, and Jay Lucas Chacon.

The opera played on Dec. 13 and 14, 2019. You can see an excerpt of the opera.

Scott Little, a student at Kent State University in Ohio, created an opera based on” The Story of an Hour” in 2018.

Accurate texts of “The Story of an Hour”

The Complete Works of Kate Chopin. Edited by Per Seyersted. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969, 2006.

Kate Chopin: A Vocation and a Voice. Edited by Emily Toth. New York: Penguin, 1991.

Kate Chopin: Complete Novels and Stories. Edited by Sandra Gilbert. New York: Library of America, 2002.

Books and Book Chapters about “The Story of an Hour”

Fox, Heather A. Arranging Stories: Framing Social Commentary in Short Story Collections by Southern Women Writers. University Press of Mississippi, 2022.

Ostman, Heather, and Kate O’Donoghue, eds. Kate Chopin in Context: New Approaches. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Rajakumar, Mohanalakshmi and Geetha Rajeswar. “What Did She Die of? ‘The Story of an Hour’ in the Middle East Classroom”: 173–85.

Wan, Xuemei. Beauty in Love and Death — An Aesthetic Reading of Kate Chopin’s Works [in Chinese]. China Social Sciences P, 2012.

Gale, Robert L. Characters and Plots in the Fiction of Kate Chopin. Jefferson, N C: McFarland, 2009.

Beer, Janet, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 2008.

Ostman, Heather, ed. Kate Chopin in the Twenty-First Century: New Critical Essays. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars, 2008.

Beer, Janet. Kate Chopin, Edith Wharton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Studies in Short Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Stein, Allen F. Women and Autonomy in Kate Chopin’s Short Fiction. New York: Peter Lang, 2005.

Perrin-Chenour, Marie-Claude. Kate Chopin: Ruptures [in French]. Paris, France: Belin, 2002.

Evans, Robert C. Kate Chopin’s Short Fiction: A Critical Companion. West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill, 2001.

Beer, Janet. Kate Chopin, Edith Wharton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Studies in Short Fiction. New York: Macmillan–St. Martin’s, 1997.

Koloski, Bernard. Kate Chopin: A Study of the Short Fiction. New York: Twayne, 1996.

Boren, Lynda S., and Sara deSaussure Davis (eds.), Kate Chopin Reconsidered: Beyond the Bayou. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1992.

Ewell, Barbara C. “Kate Chopin and the Dream of Female Selfhood”: 157–65.

Toth, Emily, ed. A Vocation and a Voice by Kate Chopin. New York: Penguin, 1991.

Showalter, Elaine. Sister’s Choice: Tradition and Change in American Women’s Writing. Oxford, England: Oxford UP, 1991.

Papke, Mary E. Verging on the Abyss: The Social Fiction of Kate Chopin and Edith Wharton. New York: Greenwood, 1990.

Bonner, Thomas Jr., The Kate Chopin Companion. New York: Greenwood, 1988.

Ewell, Barbara C. Kate Chopin. New York: Ungar, 1986.

Skaggs, Peggy. Kate Chopin. Boston: Twayne, 1985.

Stein, Allen F. After the Vows Were Spoken: Marriage in American Literary Realism. Columbus: Ohio UP, 1984.

Cahill, Susan. Women and Fiction: Short Stories by and about Women. New York: New American Library, 1975.

Leary, Lewis, ed. The Awakening and Other Stories by Kate Chopin. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969.

Rankin, Daniel, Kate Chopin and Her Creole Stories. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1932.

Selected articles about “The Story of an Hour”

Some of the works listed here may be available online through university or public libraries.

Hu, Aihua. “The Art of Repetition in ‘The Story of an Hour’.” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes, and Reviews, vol. 35, no. 4, Oct. 2022, pp. 458–63.

Hu, Aihua. “’The Story of an Hour’: Mrs. Mallard’s Ethically Tragic Song.” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes, and Reviews, vol. 35, no. 2, Apr. 2022, pp. 141–47.

Ramos, Paula Pope. “She felt it, creeping out of the sky”: Loucura e Morte como Libertação na Ficção de Mulheres do Século XIX.” [Madness and death as liberation in 19th century women’s fiction.] Itinerários–Revista de Literatura, issue 54, Jan-June 2022, pp. 73-83.

Ahmetspahić, Adisa, and Damir Kahrić. “It’s a Man’s World: Re-Examination of the Female Perspective in Chopin’s ‘Désirée’s Baby’ and ‘The Story of an Hour.’” ESSE Messenger, vol. 29, no. 1, Summer 2020, pp. 23–37.

Geriguis, Lora E. “The ‘It’ and the ‘Joy That Kills:’ An Ecocritical Reading of Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” Explicator, vol. 78, no. 1, Jan. 2020, pp. 5–8.

Yazgı, Cihan. “Tragic Elements and Discourse-Time in ‘The Story of an Hour.’” The Explicator, vol. 78, no. 3–4, July 2020, pp. 147–152.

Koloski, Bernard. “Kate Chopin.” Oxford Bibliographies in American Literature, edited by Jackson Bryer, Oxford University Press, 2020 [update].

Yazgı, Cihan. “Tragic Elements and Discourse-Time in ‘The Story of an Hour.’” The Explicator, vol. 78, no. 3–4, July 2020, pp. 147–152.

Distel, Kristin M. “‘Free! Body and Soul Free!’: The Docile Female Body in Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” New Woman’s Writing: Contextualising Fiction, Poetry and Philosophy, Subashish Bhattacharjee and Girindra Narayan Ray, editors. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018, pp. 65–78.

Doloff, Steven. “Kate Chopin’s Lexical Diagnostic in ‘The Story of an Hour’.” Notes And Queries 61 (259).4 (2014): 580–81.

Berenji, Fahimeh Q. “Time and Gender in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wall-Paper’ and Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” Tarih Kültür Ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi/Journal of History, Culture & Art Research, vol. 2, no. 2, 2013, pp. 221–234.

Sümer, Sema Zafer. “‘The Story of an Hour’ Or The Story of a Lost Lady in The Shadow of the Patriarchy’s Ideology.” Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 28.(2012): 191-196.

Diederich, Nicole. “Sharing Chopin: Teaching ‘The Story of an Hour’ to Specialized Populations.” Arkansas Review 43 (2012): 116–20.

Mayer, Gary H. “A Matter of Behavior: A Semantic Analysis of Five Kate Chopin Stories.” ETC.: A Review of General Semantics 67.1 (2010): 94-104.

Shen, Dan. “Wen Xue Ren Zhi: Ju Ti Yu Jing Yu Gui Yue Xing Yu Jing.” [in Chinese] Foreign Literature Studies/Wai Guo Wen Xue Yan Jiu 32.5 (2010): 122–8.

Jamil, S. Selina. “Emotions in ‘The Story of an Hour’.” Explicator 67.3 (2009): 215-220.

Wan, Xuemei. “Kate Chopin’s View on Death and Freedom in The Story of an Hour.” English Language Teaching 2.4 (2009): 167-170.

Emmert, Scott D. “Naturalism and the Short Story Form in Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” Scribbling Women & the Short Story Form: Approaches by American & British Women Writers. 74-85. New York, NY: Peter Lang, 2008.

Chen, Hui and Chang Wei. “Meng Jing Shi Fen De Fen Ceng Gou Si Jie Du.” [in Chinese] Qilu Xue Kan/Qilu Journal 4 (2007): 111–4.

Cunningham, Mark. “The Autonomous Female Self and the Death of Louise Mallard in Kate Chopin’s ‘Story of an Hour’.” English Language Notes 42 (2004): 48-55.

Deneau, Daniel P. “Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” Explicator 61 (2003): 210-13.

Berkove, Lawrence I. “Fatal Self-Assertion in Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” American Literary Realism 32 (Winter 2000): 152-58.

Toth, Emily. Unveiling Kate Chopin. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 1999.

Benfey, Christopher. Degas in New Orleans: Encounters in the Creole World of Kate Chopin and George Washington Cable. Berkeley: U of California P, 1997.

Johnson, Rose M. “A Rational Pedagogy for Kate Chopin’s Passional Fiction: Using Burke’s Scene-Act Ratio to Teach ‘Story’ and ‘Storm’.” Conference of College Teachers of English Studies 60 (1996): 122-28.

Koloski, Bernard. “The Anthologized Chopin: Kate Chopin’s Short Stories in Yesterday’s and Today’s Anthologies.” Louisiana Literature 11 (1994): 18-30.

Mitchell, Angelyn. “Feminine Double Consciousness in Kate Chopin’s ‘The Story of an Hour’.” CEAMagazine 5.1 (1992): 59–64.

Papke, Mary E. Verging on the Abyss: The Social Fiction of Kate Chopin and Edith Wharton. New York: Greenwood, 1990.

Ewell, Barbara C. Kate Chopin. New York: Ungar, 1986.

Miner, Madonne M. “Veiled Hints: An Affective Stylist’s Reading of Kate Chopin’s ‘Story of an Hour’.” Markham Review 11 (1982): 29–32.

Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969.

Cahill, Susan. Women and Fiction: Short Stories by and about Women. New York: New American Library, 1975.