“Regret” is Kate Chopin’s short story about a fiftyish, unmarried woman who becomes responsible for the care of her neighbor’s four children.

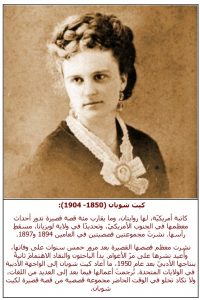

Above photo: an announcement of a short film based on Kate Chopin’s “Regret”

By the Editors of KateChopin.org

Read the story in a PDF

Characters

Time and place

Themes

When the story was written and published

Questions and answers

What other scholars say about the story

“Regret” in Arabic

Accurate texts

New All of Kate Chopin’s short stories in Spanish

Articles and book chapters about the story

Books that discuss Kate Chopin’s short stories

New: A film based on “Regret”

“Regret” online and in print

You can read the story and download it in our accurate, printable, and searchable PDF file, although if you’re citing a passage from this or other Kate Chopin stories for research purposes, it’s a good idea to check your citation against one of these printed texts.

“Regret” characters

- Mamzelle Aurélie: People call Aurélie “Mamzelle”–mademoiselle–French for an unmarried woman

- Ponto: Aurélie’s dog

- Odile: Aurélie’s neighbor

- Elodie: Odile’s youngest daughter

- Ti Nomme: [Petit Homme–French for “Little Fellow”], Odile’s son

- Marline: Odile’s daughter

- Marcélette: Odile’s daughter

- Valise: working for Odile

- Aunt Ruby: Aurélie’s cook

“Regret” time and place

The narrative takes place at the farm of Mamzelle Aurélie–apparently in rural Louisiana.

“Regret” themes

As we explain in the questions and answers below, readers often focus on the idea of motherhood in the story and how Kate Chopin approaches that subject. Readers are often troubled by Chopin’s use of what today is offensive racial phrasing. And some readers struggle with the dialect spoken by characters in the story.

You can read about finding themes in Kate Chopin’s stories and novels on the Themes page of this site.

When Kate Chopin’s “Regret” was written and published

The story was written on September 17, 1894 (two days before Chopin wrote “The Kiss”). It was first published in Century in May, 1895, and included in A Night in Acadie, Chopin’s second published volume of short stories (1897).

You can find out when Kate Chopin wrote each of her short stories and when and where each was first published.

Questions and answers about “Regret”

Q: Is Kate Chopin advocating for motherhood in this story?

A: Scholars have been discussing that for a long time. Peggy Skaggs argues that “Regret” develops the idea that “to experience life richly a woman needs a child or children to love and care for.” Mamzelle Aurélie, Skaggs says, “lacks that important part of a woman’s life, the maternal relationship.” And Mary Papke adds that in this story “Chopin depicts the female strength granted to mothers.”

But in the recent Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin Michael Worton notes that “Adrienne Rich argues in Of Woman Born, [that] we need to differentiate between motherhood as an institution and motherhood as a series of individual experiences and practices. It is with the institutional dimension that Chopin mainly engages in her fiction. However, it is interesting to note that she also gives examples of motherhood as creative and reparative, especially when motherhood is an adopted rather than natural role.”

Q: At one point in this story Kate Chopin writes, “There was a pleasant odor of pinks in the air.” That phrase reminds me of something else Chopin wrote, but I can’t remember what. Do you know what it could be?

A: You may be thinking of the closing sentence of The Awakening: “There was the hum of bees, and the musky odor of pinks filled the air.”

Q: Can you help me understanding the dialect some of Chopin’s characters are speaking in this story?

A: You might try reading those passages aloud–or you might find a native speaker of English who can read them aloud with feeling. Chopin is capturing what her characters sound like as they speak, so it may be helpful to hear the story, rather than read it.

For example, here’s a passage from the beginning of “Regret” in which Odile is speaking to Mamzelle Aurélie:

“It’s no question, Mamzelle Aurélie; you jus’ got to keep those youngsters fo’ me tell I come back. Dieu sait, I would n’ botha you with ’em if it was any otha way to do! Make ’em mine you, Mamzelle Aurélie; don’ spare ’em. Me, there, I’m half crazy between the chil’ren, an’ Léon not home, an’ maybe not even to fine po’ maman alive encore!”

If you could hear that read aloud, you might understand better. In today’s standard American English, the character is saying something like:

“There’s no question, Mamzelle Aurélie; you just have to keep those youngsters for me until I come back. Dieu sait [French: God knows], I wouldn’t bother you with them if there were any other way! Make them mind you [listen to you], Mamzelle Aurélie; don’t spare them. Me, there, I’m half crazy [worried] about the children, and Léon [her husband] not home, and maybe not even to find my poor maman [French; mother] alive encore [French: still]!”

In this and most other Chopin stories, if you misunderstand some of the dialectal expressions, it’s not likely to lead to you misunderstand what’s happening in the story.

Q: I’m really troubled to see Chopin speak of “negroes” in this story. Isn’t that deeply offensive language?

A: This painful subject requires a sense of historical imagination, historical empathy. Chopin’s language here is a picture of the way people in her time spoke to one another. Words like “darkey” and “Negro,” offensive for us in the twenty-first century, were used familiarly by people of color and white people in Chopin’s Louisiana, usually without intended rancor. Kate Chopin reproduced such language in her characters’ speech, as she reproduced people’s dialectal patterns. For her, as for Mark Twain and others of her generation, recording accurately the way people spoke was an important part of being a good writer.

Louisiana at the time was just a decade or so away from slavery. Chopin does not pretend that the color line is gone, that Blacks enjoy complete freedom and equality, or that everyone lives in racial harmony with everyone else. There are racial tensions in several of her stories.

Chopin was, of course, a nineteenth-century, white, Southern woman, but she was also deeply steeped in French culture, being bilingual and bi-cultural from birth. She shares both American and European attitudes toward race, and she always sees more than her characters do.

There’s been a good deal written about Chopin and race. If you want to explore the subject you might start by reading articles by Anna Shannon Elfenbein, Helen Taylor, and Elizabeth Ammons in the Norton Critical Edition of The Awakening, and you might look at Bonnie James Shaker’s Coloring Locals. For a defense of Chopin you might start by checking Emily Toth’s Kate Chopin and Bernard Koloski’s Kate Chopin: A Study of the Short Fiction, and online you could read Elizabeth Fox-Genovese’s comments on the Kate Chopin: A Re-Awakening site. You can find information about these and other publications about Chopin and race at the bottom of the Awakening page and the Short Stories page of this site, as well as on pages devoted to individual stories, like “Désirée’s Baby.”

You can read more questions and answers about Kate Chopin and her work, and you can contact us with your questions.

What other scholars say about “Regret”

Per Seyersted devotes five pages to a discussion of “Regret,” comparing its content and its form to a short story by Guy de Maupassant. And he emphasizes Kate Chopin’s ties to France and Ireland. “Her writing demonstrated an instinctive artistic sense which made use of the best of the Celtic and Gallic traditions. She had learned to apply her in inborn French simplicity and clarity, logic and precision, and the Gallic sense of form, economy of means, and restraint, together with the pathos and humor, the warmth and gaiety of the Irish.”

In her analysis of the story, Barbara Ewell probes “the value of other-centeredness” and “the limits and costs of self-sufficiency.” By the end of “Regret,” Ewell writes, “Aurélie has glimpsed a life that has revealed the insufficiency of her own.”

كيت شوبان

A Third Kate Chopin Short Story in Arabic

We are grateful to hear from Professor Lina Ibrahim at Bayan University College, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, who tells us that she has translated “Regret,” Kate Chopin’s short story, into Arabic. It is published in al-adab.com, an online literary magazine. You can read “Regret” and Lina Ibrahim’s earlier translations, “The Story of an Hour” and “Désirée’s Baby,” on the al-adab.com website.

We asked Professor Ibrahim why she chose to translate these three stories. She replied:

“Each story struck a chord with me. The three women: Désirée, Louise, and Mamzelle Aurélie represent three types of women caught up in situations that other women can relate to until the end of time.

“Désirée faces what so many women face: If there’s a problem, blame it on the woman. Her husband, recognizing the color of his son, is unable to blame anyone but his young beautiful wife. As a man, he thinks of himself as infallible and believes the woman must be responsible for a sin and must be punished (for a crime, it turns out, she did not commit).

“Louise represents miserable women caught in a traditional marriage. They have everything, yet they aren’t happy. The moment of revelation that comes to Louise while grieving the death of her husband brings with it a state of ecstasy. Now she is free, now she understands that her marriage was a prison from which she is finally released. I do believe that many women nowadays find themselves in similar marriages.

“Mamzelle Aurélie is a spinster by choice. She realizes too late that the outcome of her decision to not marry is a life of loneliness. What I relate to in the story is her realization that the children made her aware of what she was missing—not the absence of a male partner, not marriage as an institution, but the joy that comes with having children, connecting with and taking care of them. Here lies the regret of her choice.”

For students and scholars

Accurate texts of “Regret”

The Complete Works of Kate Chopin. Edited by Per Seyersted. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969, 2006.

Bayou Folk and A Night in Acadie. Edited by Bernard Koloski. New York: Penguin, 1999.

Kate Chopin: Complete Novels and Stories. Edited by Sandra Gilbert. New York: Library of America, 2002.

Articles and book chapters about “Regret”

Ostman, Heather, and Kate O’Donoghue, eds. Kate Chopin in Context: New Approaches. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. The book contains this essay:

Ostman, Heather. “Maternity vs. Autonomy in Chopin’s ‘Regret’”: 101–15.

Worton. Michael.” Reading Kate Chopin through contemporary French feminist theory” In The Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin. Ed. Janet Beer. Cambridge UP, 2008. 105–17.

Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969. 125–30.

Books that discuss Chopin’s short stories

Fox, Heather A. Arranging Stories: Framing Social Commentary in Short Story Collections by Southern Women Writers. University Press of Mississippi, 2022.

Ostman, Heather. Kate Chopin and Catholicism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Ostman, Heather, and Kate O’Donoghue, eds. Kate Chopin in Context: New Approaches. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. The book contains these essays:

Koloski, Bernard. “Chopin’s Enlightened Men”: 15–27.

Walker, Rafael. “Kate Chopin and the Dilemma of Individualism”: 29–46.

Armiento, Amy Branam. “‘A quick conception of all that this accusation meant for her’: The Legal Climate at the Time of ‘Désirée’s Baby’”: 47–64.

Rossi, Aparecido Donizete. “The Gothic in Kate Chopin”: 65–82.

Gil, Eulalia Piñero. “The Pleasures of Music: Kate Chopin’s Artistic and Sensorial Synesthesia”: 83–100.

Ostman, Heather. “Maternity vs. Autonomy in Chopin’s ‘Regret’”: 101–15.

Merricks, Correna Catlett. “‘I’m So Happy; It Frightens Me’: Female Genealogy in the Fiction of Kate Chopin and Pauline Hopkins”: 145–58.

Sehulster, Patricia J. “American Refusals: A Continuum of ‘I Prefer Not Tos’ as Articulated in the Work of Chopin, Hawthorne, Harper, Atherton, and Dreiser”: 159–72.

Rajakumar, Mohanalakshmi and Geetha Rajeswar. “What Did She Die of? ‘The Story of an Hour’ in the Middle East Classroom”: 173–85.

O’Donoghue, Kate. “Teaching Kate Chopin Using Multimedia”: 187–202.

James Nagel. Race and Culture in New Orleans Stories: Kate Chopin, Grace King, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and George Washington Cable. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2014.

Brosman, Catharine Savage. Louisiana Creole Literature: A Historical Study. UP of Mississippi, 2013.

Wan, Xuemei. Beauty in Love and Death—An Aesthetic Reading of Kate Chopin’s Works [in Chinese]. China Social Sciences P, 2012.

Hebert-Leiter, Maria. Becoming Cajun, Becoming American: The Acadian in American Literature from Longfellow to James Lee Burke. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2009.

Gale, Robert L. Characters and Plots in the Fiction of Kate Chopin. Jefferson, N C: McFarland, 2009.

Beer, Janet, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Kate Chopin. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 2008. The book contains these essays:

Knights, Pamela. “Kate Chopin and the Subject of Childhood”: 44–58.

Castillo, Susan. “’Race’ and Ethnicity in Kate Chopin’s Fiction”: 59–72.

Joslin, Katherine. “Kate Chopin on Fashion in a Darwinian World”: 73–86.

Worton, Michael. “Reading Kate Chopin through Contemporary French Feminist Theory”: 105–17.

Horner, Avril. “Kate Chopin, Choice and Modernism”: 132–46.

Taylor, Helen. “Kate Chopin and Post-Colonial New Orleans”: 147–60.

Ostman, Heather, ed. Kate Chopin in the Twenty-First Century: New Critical Essays. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars, 2008. The book contains these essays:

Kornhaber, Donna, and David Kornhaber. “Stage and Status: Theatre in the Short Fiction of Kate Chopin”: 15–32.

Thrailkill, Jane F. “Chopin’s Lyrical Anodyne for the Modern Soul”: 33–52.

Johnsen, Heidi. “Kate Chopin in Vogue: Establishing a Textual Context for A Vocation and a Voice”: 53–69.

Batinovich, Garnet Ayers. “Storming the Cathedral: The Antireligious Subtext in Kate Chopin’s Works”: 73–90.

Kirby, Lisa A. “‘So the storm passed . . .’: Interrogating Race, Class, and Gender

in Chopin’s ‘At the ’Cadian Ball’ and ‘The Storm’”: 91–104.

Frederich, Meredith. “Extinguished Humanity: Fire in Kate Chopin’s ‘The Godmother’”: 105–18.

Beer, Janet. Kate Chopin, Edith Wharton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Studies in Short Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Stein, Allen F. Women and Autonomy in Kate Chopin’s Short Fiction. New York: Peter Lang, 2005.

Lohafer, Susan. Reading for Storyness: Preclosure Theory, Empirical Poetics and Culture in the Short Story. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 2003.

Shaker, Bonnie James. Coloring Locals: Racial Formation in Kate Chopin’s Youth’s Companion Stories. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2003.

Perrin-Chenour, Marie-Claude. Kate Chopin: Ruptures [in French]. Paris, France: Belin, 2002.

Evans, Robert C. Kate Chopin’s Short Fiction: A Critical Companion. West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill, 2001.

Koloski, Bernard, ed. Bayou Folk and A Night in Acadie by Kate Chopin. New York: Penguin, 1999.

Beer, Janet. Kate Chopin, Edith Wharton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Studies in Short Fiction. New York: Macmillan–St. Martin’s, 1997.

Koloski, Bernard. Kate Chopin: A Study of the Short Fiction. New York: Twayne, 1996.

Petry, Alice Hall, ed. Critical Essays on Kate Chopin. New York: G. K. Hall, 1996. The book contains these essays:

Pollard, Percival. “From Their Day in Court“: 67–70.

Reilly, Joseph J. “Stories by Kate Chopin”: 71–74.

Skaggs, Peggy. “The Boy’s Quest in Kate Chopin’s ‘A Vocation and a Voice’”: 129–33.

Dyer, Joyce [Coyne]. “The Restive Brute: The Symbolic Presentation of Repression and Sublimation in Kate Chopin’s ‘Fedora’”: 134–38.

Arner, Robert D. “Pride and Prejudice: Kate Chopin’s ‘Désirée’s Baby’”: 139–46.

Bauer, Margaret D. “Armand Aubigny, Still Passing After All These Years: The Narrative Voice and Historical Context of ‘Désirée’s Baby’”: 161–83.

Berkove, Lawrence I. “‘Acting Like Fools’: The Ill-Fated Romances of ‘At the ’Cadian Ball’ and ‘The Storm’”: 184–96.

Wagner-Martin, Linda. “Kate Chopin’s Fascination with Young Men”: 197–206.

Walker, Nancy A. “Her Own Story: The Woman of Letters in Kate Chopin’s Short Fiction”: 218–26.

Elfenbein, Anna Shannon. Women on the Color Line: Evolving Stereotypes and the Writings of George Washington Cable, Grace King, Kate Chopin. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1994.

Fick, Thomas H., and Eva Gold, guest eds. “Special Section: Kate Chopin.” Louisiana Literature: A Review of Literature and Humanities. Spring, 1994. 8–171. The special section of the journal contains these essays:

Toth, Emily. “Introduction: A New Generation Reads Kate Chopin”: 8–17.

Koloski, Bernard. “The Anthologized Chopin: Kate Chopin’s Short Stories in Yesterday’s and Today’s Anthologies”: 18–30.

Saar, Doreen Alvarez. “The Failure and Triumph of ‘The Maid of Saint Phillippe’: Chopin Rewrites American Literature for American Women”: 59–73.

Dyer, Joyce. “‘Vagabonds’: A Story without a Home”: 74–82.

Padgett, Jacqueline Olson. “Kate Chopin and the Literature of the Annunciation, with a Reading of ‘Lilacs’”: 97–107.

Day, Karen. “The ‘Elsewhere’ of Female Sexuality and Desire in Kate Chopin’s ‘A Vocation and a Voice’”: 108–17.

Cothern, Lynn. “Speech and Authorship in Kate Chopin’s ‘La Belle Zoraïde’”: 118–25.

Lundie, Catherine. “Doubly Dispossessed: Kate Chopin’s Women of Color”: 126–44.

Ellis, Nancy S. “Sonata No. 1 in Prose, the ‘Von Stoltz’: Musical Structure in an Early Work by Kate Chopin”: 145–56.

Ewell, Barbara C. “Making Places: Kate Chopin and the Art of Fiction”: 157–71.

Boren, Lynda S., and Sara deSaussure Davis (eds.), Kate Chopin Reconsidered: Beyond the Bayou. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1992. The book contains these essays:

Toth, Emily. “Kate Chopin Thinks Back Through Her Mothers: Three Stories by Kate Chopin”: 15–25.

Bardot, Jean. “French Creole Portraits: The Chopin Family from Natchitoches Parish”: 26–35.

Thomas, Heather Kirk. “‘What Are the Prospects for the Book?’: Rewriting a Woman’s Life”: 36–57.

Black, Martha Fodaski. “The Quintessence of Chopinism”: 95–113.

Ewell, Barbara C. “Kate Chopin and the Dream of Female Selfhood”: 157–65.

Davis, Sara deSaussure. “Chopin’s Movement Toward Universal Myth”: 199–206.

Blythe, Anne M. “Kate Chopin’s ‘Charlie’”: 207–15.

Ellis, Nancy S. “Insistent Refrains and Self-Discovery: Accompanied Awakenings in Three Stories by Kate Chopin”: 216–29.

Toth, Emily, ed. A Vocation and a Voice by Kate Chopin. New York: Penguin, 1991.

Showalter, Elaine. Sister’s Choice: Tradition and Change in American Women’s Writing. Oxford, England: Oxford UP, 1991.

Papke, Mary E. Verging on the Abyss: The Social Fiction of Kate Chopin and Edith Wharton. New York: Greenwood, 1990.

Elfenbein, Anna Shannon. Women on the Color Line: Evolving Stereotypes and the Writings of George Washington Cable, Grace King, Kate Chopin. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1989.

Taylor, Helen. Gender, Race, and Region in the Writings of Grace King, Ruth McEnery Stuart, and Kate Chopin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1989.

Bonner, Thomas Jr., The Kate Chopin Companion. New York: Greenwood, 1988.

Bloom, Harold, ed. Kate Chopin. New York: Chelsea, 1987. The book contains these essays:

Ziff, Larzer. “An Abyss of Inequality”: 17–24.

Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. “The Fiction of Limits: ‘Désirée’s Baby’”: 35–42.

Dyer, Joyce C. “Gouvernail, Kate Chopin’s Sensitive Bachelor”: 61–69.

Dyer, Joyce C. “Kate Chopin’s Sleeping Bruties”: 71–81.

Gardiner, Elaine. “‘Ripe Figs’: Kate Chopin in Miniature”: 83–87.

Ewell, Barbara C. Kate Chopin. New York: Ungar, 1986.

Skaggs, Peggy. Kate Chopin. Boston: Twayne, 1985.

Toth, Emily, ed. Regionalism and the Female Imagination. New York: Human Sciences Press, 1984.

Stein, Allen F. After the Vows Were Spoken: Marriage in American Literary Realism. Columbus: Ohio UP, 1984.

Huf, Linda. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman: The Writer as Heroine in American Literature. New York: Ungar, 1983.

Christ, Carol P. Diving Deep and Surfacing: Women Writers on Spiritual Quest. Boston: Beacon, 1980.

Springer, Marlene. Edith Wharton and Kate Chopin: A Reference Guide. Boston: Hall, 1976.

Cahill, Susan. Women and Fiction: Short Stories by and about Women. New York: New American Library, 1975.

Seyersted, Per, ed. “The Storm” and Other Stories by Kate Chopin: With The Awakening. Old Westbury: Feminist P, 1974.

Freedman, Florence B., et al. Special Issue: Whitman, Chopin, and O’Faolain. WWR, 1970.

Leary, Lewis, ed. The Awakening and Other Stories by Kate Chopin. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1969.

Rankin, Daniel, Kate Chopin and Her Creole Stories. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1932.